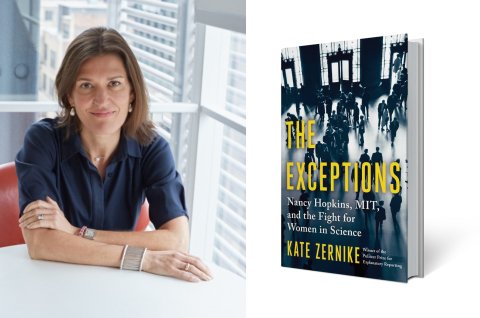

Nancy Hopkins and 15 colleagues at MIT banded together to demonstrate gender inequities among faculty resources in the '90s. MIT agreed, and the changes they helped bring about launched widespread change for women throughout academia and the sciences. How did that happen? Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Kate Zernike tells their story in her new book, The Exceptions (Scribner, February). In this Q&A, she discusses the advances they helped bring about, the issues still faced by women in STEM and what the key is to providing equal opportunity to girls and women in the sciences.

Q _ Why write this book? Why now?

A _ I started thinking about doing this book in January 2018, just as the #MeToo movement was surging. Those egregious cases made me reflect on the kind of discrimination the women at MIT had talked about in 1999: the subtle ways women are marginalized in the workplace, especially as they get older. I think it is more pervasive, and more insidious. The great insight of the MIT women was that it wasn't enough to open doors to women, you had to make sure you valued and treated them equally into their careers. It struck me that the problems faced by women in science crystallize the broader problem, which is that we still don't take women as seriously in intellectual and professional settings. This story is even more relevant now, as the country again debates whether we still need affirmative action. These women trusted that science, with its emphasis on data and facts, would be a pure meritocracy. They discovered there is no such thing.

Nancy Hopkins and her colleagues' efforts led to advances in academic sciences. Did this translate to other areas of academia and STEM careers more broadly?

When the MIT Report came out, there had never been a single female department head at MIT. Now the university is run by women, from the board of trustees to the president's office and the dean of science. (So is the state of Massachusetts and the city of Boston.) There was one female president of the Ivy League at the time, this fall, six of those eight institutions will be led by women. That's a small and elite subset, but those universities can set trends. There are other subtle changes: when the MIT women started looking into the problem, no female professors were taking maternity leave because of the stigma. Now female scientists on many campuses say it's no longer the exception to see female colleagues dropping off their children at day care centers on campus, many of which did not exist in 1999. It is routine for universities to stop the tenure clock for women (and men) when they have children. The president of the National Academy of Sciences and President Biden's top three science advisers are women, as were the people leading the development of vaccines as the world fought the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, very few women win Nobel Prizes in science, which reminds us we have a long way to go in nurturing and valuing the contributions of women.

Given the pay disparity between women and men in STEM jobs today, how significant was the MIT group? What's next in the fight?

Women in most fields still earn less than men for the same work. Changing that can't be on one group of women at one university, it's up to the men and women leading companies and universities. The MIT women didn't even think the report would be read beyond their own campus. But the publicity around their story prompted other universities to do similar audits. It also led the National Science Foundation to establish a program that has addressed differential treatment in teaching assignments, awarding of grants and bias in hiring.

The attrition rate for women in science and engineering schools is still disproportionately high. And a report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in 2018 found that about half of all women on those faculties experience sexual harassment. Of those cases, a small percentage involved sexual coercion. The biggest problem by far was what the MIT women had identified, what the report called "gender harassment." It's the sexist putdowns about women in science, crude comments that have the effect of making women feel they are not welcome in these environments. This is especially true for women who are doubly marginalized: women of color, lesbian women or those who are what we traditionally consider masculine in appearance or behavior.

When then-president of Harvard, Larry Summers commented on women's "issues of intrinsic aptitude," it set off another firestorm of debate on the subject. Is women's success in the field still seen as "an exception" to many?

I followed that story pretty closely in 2005, but I was still shocked when I went back to see the flood of articles at the time defending Larry Summers, even when there was plenty of research to refute what he said. Some of his ideas—not just that women lacked intrinsic aptitude but that they didn't want to work 80-hour weeks—have been around since the earliest part of the last century. I do think now there is more awareness. "The exceptions" also refers to the way these women explained away the small ways in which they were being discriminated against; they assumed it had to do with the particular circumstances, or blamed themselves. I think now we better understand the systemic bias.

Nancy's report has never been released publicly. Why? Do you think information in it could help the cause for current and future women seeking to crack the glass ceiling?

MIT did not release the full report because it contained stories from or about female professors that had been told with the promise of confidentiality. You couldn't make those stories anonymous; even saying "a junior faculty member in math" would identify the woman because there were only one or two. The stories are in the book, and I do think they illustrate the assumptions and patterns women still have to work against, the pitfalls to avoid.

What was the most surprising thing you learned when researching this book?

It should not surprise me, or us, but I was reminded of how long we've been talking about the same problems, and even coming up with solutions, but not doing anything. President Kennedy's Commission on Women in 1963 recommended paid maternity leave; it took decades to get it. Research in the 1970s showed that all of us—women and men—value the same resume less if it has a woman's name instead of a man's on it. I was reminded that every generation thinks it has solved the problem, only for every generation to discover it anew.

What's the key to providing equal opportunity to girls and women in the sciences?

Changing attitudes is key, as institutions hire and as we talk about who is doing the most significant work in science. Who do we think of when we hear the word "genius"—research shows us it tends to be men. At MIT, the School of Engineering had remarkable success hiring more women after this report, because of a male dean who refused to accept when search committees came back, as they so often had, and said there was no qualified woman to hire. He said: Look harder.