Twenty years ago, when Vironika Wilde was 12 years old, she began to lie. A lot. She lied about her age and her weight. She lied about having a speaking role on the hit TV show Degrassi when she had only been an extra. She lied that she had been in a car when a drive-by shooting occurred. Throughout her teen years and into her twenties, she lied constantly and blatantly, with little worry over whether or not her preposterous stories were believable.

"When you're in the habit of doing it, it's hard to stop," Wilde says. "The lies I told as a kid were pretty easy to figure out. But as I got older, I thought my lies were really clever."

Not until she suffered a mental breakdown in 2012 did Wilde decide she had to change. Like a recovering alcoholic, she even went back to old friends and confessed about her lies. "When I finally started telling the truth," she says, "for the first time I got the reactions from people that I always thought I would get from lying."

Now an author and poet living in Toronto, Wilde says the lies slipped away once she began to love and accept her true self.

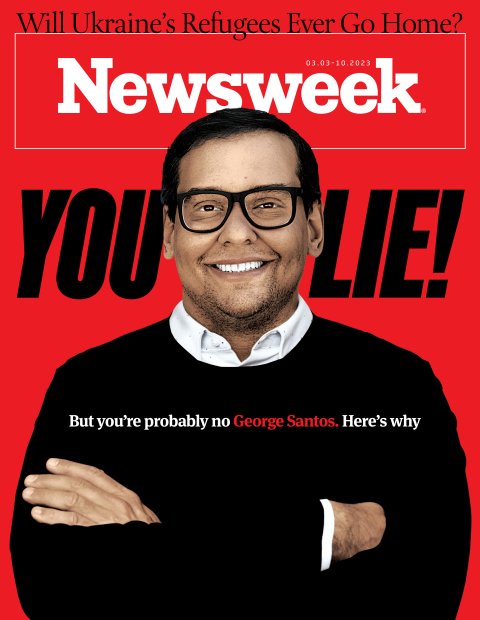

If only George Santos had learned the same lesson.

Within weeks of winning his first race for Congress in November, Santos was outed as a prolific, outrageous liar. He lied about where he went to high school and college, about being Jewish and having a grandmother who died in the Holocaust (he isn't and she didn't), about working in finance at Citigroup and Goldman Sachs, about where his campaign money came from and how he spent it, about starting an animal charity, about his mother dying on 9/11 and about having four employees who died at the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016.

Of course, Santos is hardly alone in his lying. Former President Donald Trump is under investigation for lying about the results of the 2020 election (even as a significant portion of the electorate insist that President Joe Biden is the liar.) Such stories go a long way toward explaining why so many people think not only politicians, but also car salespeople, lawyers, real estate agents and (ahem) journalists are not to be trusted. As a Gallup poll released on January 10 shows, fewer than 25 percent of respondents considered people in those professions to rate high or very high for honesty and ethical standards. A whopping 62 percent rated members of Congress as low or very low.

But how common is lying, really? As it happens, science has an answer: not very. Aside from a small percentage of people who, like Santos, are prolific liars, most of us are pretty darn honest. We also have a strong natural tendency to believe what others tell us, studies have found—which is how the Santosians of the world get away with it.

Lying, in fact, can be a good thing, science has found: In children it's a sign of growing cognitive maturity, while in adults it protects against unnecessarily harming others' feelings. In business negotations, exaggerations and even outright lies are so common that anyone who buys a home without first having it inspected is considered a fool. Researchers have even begun to learn why most of us are bad at detecting when someone is lying (and found new ways to do much better).

The truth about lies and liars turns out to be surprisingly reassuring, according to a wealth of new scientific studies. Reassuring, that is, if you believe in science.

Teach Your Children to Lie

If you think Santos is the LeBron James of lying, think again. Liars have been around since Cain killed Abel and lied about it to God, as told in Genesis. In the late 1600s, a British swindler named William Chaloner scammed the Royal Mint and Bank of England before being proved guilty by Sir Isaac Newton. In the 1920s, Charles Ponzi cooked up a type of pyramid scheme that now bears his name. In 2008, Bernard L. Madoff was found to be running the biggest Ponzi scheme in history, having swindled clients out of $64.8 billion.

My all-time personal favorite lie was one of the most common, ordinary kind, carried out in partnership with my best friend when I was 13. To see the band Three Dog Night at Madison Square Garden in New York City, I told my mother that I was sleeping over at his house. He told his mother that he was sleeping over at my house. Neither ever found out.

Lying turns out to be a very teenage thing to do, as most parents learn."Lying peaks in adolescence and then declines all through adulthood and into the senior years," says Victoria Talwar, professor of developmental psychology at McGill University and author of The Truth About Lying: Teaching Honesty to Children at Every Age and Stage (APA LifeTools, 2022).

Preschoolers lie, too, but not very convincingly, Talwar says, and usually just to get out of trouble. ("Did you eat the last cookie?" "No," the toddler says, with chocolate smudged on her face.) By elementary school, the lies become more complex, and are often aimed at puffing up their reputation. "A boy in my son's class said he had taken a trip to Mexico and brought back a parrot," Talwar says. "He had no parrot. He was trying to get attention."

Given how common the occasional childhood lie can be, Talwar urges parents not to freak over it. "I've seen parents get very upset," she says. "The worst time by far was when I had a parent who flipped out because her four-year-old had lied to her. She was a fundamentalist Christian. She called her child a sinner."

Lying in very young children is actually a sign of cognitive development, according to Kang Lee, a professor of developmental psychology at the University of Toronto who has been studying deception in children and adults for 30 years.

"Most two-year-olds are very honest," Lee says. "Only about 25 percent will lie when we test them in our studies. By three, about 50 percent will lie. At four years, about 80 percent lie. By the time they get to elementary school, almost everybody lies in my studies."

Learning to lie requires children to have the cognitive self-control to suppress the truth and the understanding of something simple but profound: that what they know might be different from what others know. If Liam puts a toy in the closet while Celeste is out of the room, he needs to grasp that she won't know where it is when she returns. Lee calls this skill "mind reading."

"It turns out that those kids who lie at an early age have better mind-reading abilities and better self-control than those who do not lie," Lee says. "That's very surprising. We always thought that kids who lie lack moral character, that they have lower IQ, that they must be worse at everything. Instead, it looks like lying is a normative developmental behavior."

So important is "mind reading" to a child's social development that Lee has taught it to three-year-olds who were not yet able to lie. Over a period of 10 days, he has them play games to demonstrate that what he knows and likes can be different from what the child knows and likes. For instance, he gives a child three cups with a tiny ball inside one of them. While Lee closes his eyes, he tells the child to move the ball into another cup. It might take over a week of practice, but eventually it will dawn on the kid that Lee doesn't know where it was moved to, even though the child does know. The result, Lee says, is that the child becomes better at understanding others and getting along with them (and, alas, better at lying).

Having studied some 10,000 children, Lee emphasizes that children lie relatively rarely (outside of his experiments), and usually just to be polite, as in telling Grandma that those socks she gave him for Christmas are awesome. Reassuringly, he says, "Although they lie to get out of trouble, they don't lie to get others into trouble."

Prolific Liars and the Truth Default

Scientists were once convinced that lying by adults was shockingly common, because on average their studies showed that. Then, in 2009, a group of researchers conducted a survey of 1,000 U.S. adults to dig deeper into the prevalence of lying during a 24-hour period. Sixty percent of the respondents, they found, hadn't lied once. But 5 percent of the respondents had told fully half of all the lies. The overall average, in other words, was being skewed by a tiny percentage of prolific liars.

"Most people don't lie very much—somewhere between zero and two lies per day," says Timothy R. Levine, professor and chair of the department of communications at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. "When they do lie, it tends to be about innocuous things, like saying you love the meal your friend prepared, even if you don't."

Levine's research has revolutionized our understanding of lying. Along with the fact that most of us lie very little, he also found what con artists have long known: Most of us generally expect others, even strangers, to tell us the truth. He calls this "truth-default theory" and spelled out his findings in a 2019 book Duped: Truth-Default Theory and the Social Science of Lying and Deception (University of Alabama).

"If I'm lost and ask you for directions, I don't think you're going to lie to me," he says. "We humans are by our nature a social species. In order for communication to function efficiently and effectively, we have to expect that others are telling us the truth."

Levine points to a poster in his office that says he was drafted into the NBA but turned it down to go to graduate school, then left school for a while to play in the rock band Soundgarden. "I'm 5' 8" and overweight," he says. "But you would not believe how many people come into my office, see that poster and say, 'I didn't know you played basketball.' We're all more gullible than we think we are."

Usually that's okay, because most people are fairly honest. The trouble comes when prolific liars like Santos hijack our trusting nature.

When Lying Is the Right Thing To Do

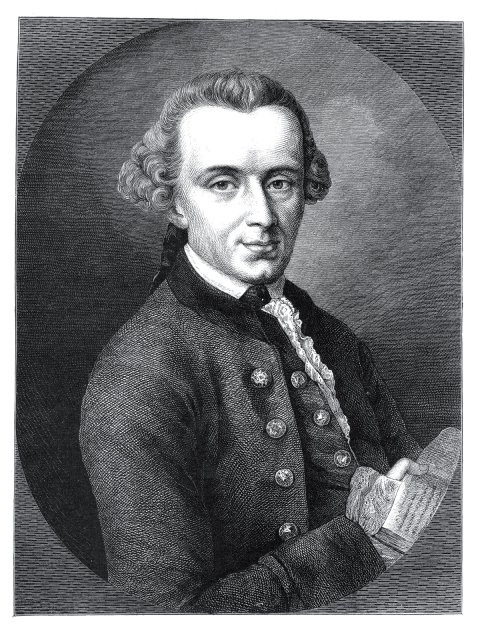

When is it acceptable, or even appropriate, to lie? Don't ask the 17th century philosopher Immanuel Kant. In his essay "On a Supposed Right to Tell Lies From Benevolent Motives," he argued that lying is never ethically right. He conjured up the extreme scenario of a murderer coming to your door while holding a knife and asking if his intended victim (hiding in a back room) is there. Even then, Kant insisted, you must tell the truth. "To be truthful (honest) in all declarations," he wrote, "is therefore a sacred unconditional command of reason, and not to be limited by any expediency."

Hogwash, most everybody else says: To condemn another to death because you place honesty above all other values is absurd. Beyond that extreme, though, the ethics can get complicated, says Emma Levine, associate professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

"Many of our most difficult ethical dilemmas involve balancing honesty with benevolence," says Levine (no relation to the truth-default Levine). "Most people think lies that prevent unnecessary hurt and harm are ethical. When the truth would cause immediate emotional harm and the person can't do anything about it, most people think that lying would be ethical."

Ethical dilemmas over telling or withholding the truth frequently arise in medical crises, she says, when for instance a person has a very low chance of survival but the doctor spins it optimistically. More mundane is the classic scenario of a wife asking her partner how she looks in a new dress.

"If you're already out to dinner, most people think it's ethical to lie and say you love it," Levine says. "But if you're still at home, and she can change, then you should tell the truth."

Even then, though, she says: "You should still be kind. 'You always look beautiful to me, but that other dress looks even better'."

Just because most people think it's okay to lie sometimes, does that necessarily mean it's truly ethical?

"I don't think it's cut and dried," she says. "When I started this work, it was surprising to me that people actually want to be lied to in certain circumstances. But my personal opinions on lying are increasingly nuanced. Lying is tempting, but the costs are often delayed."

In other words: the lies George Santos told helped him get elected, but he is now forever known as someone whose word can never be trusted. Even little white lies, told too often, can whittle away at a person's reputation, as people catch on that they're a B.S. artist.

Levine finds it especially unnerving that research has shown that people are more willing to accept a lie when it is beneficial to their belief system, social circle or political leaning. Even many supporters of former President Donald J. Trump, for instance, recognize that he routinely tells whoppers, but are willing to go along.

"We're willing to promote and follow people we recognize as liars if we see them as promoting our goals in a politically polarized world," she says. "That's unfortunate."

When You're a Fool to be Honest

Maurice Schweitzer, a professor at the Wharton School of Business, has studied business situations where lying is not only appropriate but expected."If we're playing poker, I expect you to bluff," he says. "If we negotiate, I expect you to lie about your bottom line, to say things like 'I have another interested buyer' or 'That's beyond my budget'."

In a course on negotiations that he teaches at Wharton, Schweitzer says, "I tell my students they should expect to lie and be lied to. It's self-defense. There are norms in business, and it's incumbent on you to not take every claim for granted."

If a home owner tells a potential buyer that the home does not have termites, it's up to the buyer to have the home inspected. "If you just took my word for it, it's your fault if you move in and find there are termites. Or if I'm selling you my used car and you don't get it checked out by a mechanic before buying it, that's on you."

The good news is that even the most naïvely trusting negotiators can learn quickly from experience, Schweitzer says. "We do negotiation simulations in my class," he says. "The most naïve students go in and get completely taken advantage of in their first session. 'I can't believe you lied to my face,' they say. But by their third negotiation, they're much, much more savvy."

While lying may be a commonplace in business negotiations, Schweitzer says, in other areas of life the expectations are different. "It's all about the rules of the game and what game we are playing," he says. "I don't lie to my social partners, and I don't expect a politician to lie like George Santos did. We trusted his claims about his volleyball scholarship and his Holocaust story and all the rest because nobody expected such crazy lies."

Now that we have learned our lesson, Schweitzer says, a lot more vetting of politicians' claims will be necessary. "It creates a lot of friction in the system," he says. "You tell me you graduated from this college, now I have to check with the institution. You tell me you worked at Goldman Sachs, I've got to check. It's expensive and time-consuming, because now we have somebody who exploited our trust."

How to Tell Lies from Truth

David Livingstone Smith, professor of philosophy at the University of New England, became interested in lying and deception due to what he calls "a dramatic and painful experience of being deceived. It had to do with my spouse at the time having an affair. It eventually led to our divorce."

In his book, Why People Lie (Griffin, 2007), Smith offers a simple explanation: lying usually works. Even plants lie, he says, pointing to the mirror orchid, which displays blossoms that look like female wasps. "The flower also manufactures a chemical cocktail that simulates the pheromones released by females to attract mates," he writes. The bird dung crab spider looks and smells like bird poop to hide from predators and attract prey. "Even a cat crouching to approach a mouse is deception," Smith says. And among we humans, "Certain clothing can serve as a lie, by disguising an unflattering body."

Given their ubiquity, one might think that we would be pretty good at detecting lies. But Timothy Levine has found in a series of experiments that people are only slightly better than chance at distinguishing a lie from the truth. Even then, the only reason for that slight edge is because some people are simply terrible at lying and so are easily seen through.

What makes us so bad at detecting lies? "Part of the reason is that people go on demeanor," says Levine. "They judge people based on how they come off. People who are the confident, friendly extroverts of the world tend to be believed. People who have a little social anxiety or are a little socially awkward tend not to be believed. So the more you ignore your impressions of the people and the more you listen carefully to what they're saying, the better able you will be at ferreting out deception."

Another way to be a better lie detector, Levine says, is to do some research up-front before a meeting, and then go in with questions that you already know the answer to. "It's called strategic use of evidence," he says. "If you know the truth, you can tell if someone is telling you a lie." When you can't prepare beforehand, he says, "Ask questions that you know you can fact-check later. Or ask questions to get a lot of contextual information, so you can assess plausibility."

Although a small weekly newspaper, The North Shore Leader, did raise questions about George Santos before he was elected, unfortunately the big media outlets muffed it. One question, however, remains unanswered to this day: why? Why would anyone lie about so many things that could so easily be disproved, right down to being a star on the volleyball team at Baruch University, which in fact he never attended? Seemingly unable to control his lying, he even once told a New York radio station that his team beat Harvard and Yale.

"We slayed them," he said. "Every school that came up against us, they were shaking at the time."

What leads a person to make up crazy stuff like that? Gaining an advantage—in Santos's case, winning a seat in Congress—is not enough to explain it. Instead, Santos would seem to fit the bill for a pathological liar, one whose lies flood out of control, even when there is little to gain. Nearly one-third of pathological liars grew up in a troubled home where lying was a commonplace.

"There are still people in my family who pathologically lie," Vironika Wilde says. "After I started working on it and saying I've got to stop doing it, I began to see them for what they are."

Psychologists call it pseudologia fantastica, and have found that up to 40 percent of sufferers have neurological abnormalities. Currently, however, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, considered psychiatry's "Bible," lists the condition only as a symptom of other disorders, such as antisocial or narcissistic personality disorder. Many in the field say it deserves its own listing. Timothy Levine, for instance, says the condition can be as devastating as alcoholism or compulsive gambling.

"Since the Santos story came out, I've been receiving emails from pathological liars," Levine says. "It's a compulsion that destroys their lives. They don't want to do it, but they can't stop. They get fired from their jobs. Their romantic partners dump them. It's hugely dysfunctional. That's why this is not going to end well for Santos."

For his part, Santos now says he regrets all his lies.

"I'm embarrassed and sorry for having embellished my resume," he told The New York Post. "I own up to that .... We do stupid things in life."

That might be the one truthful thing Santos has ever said.