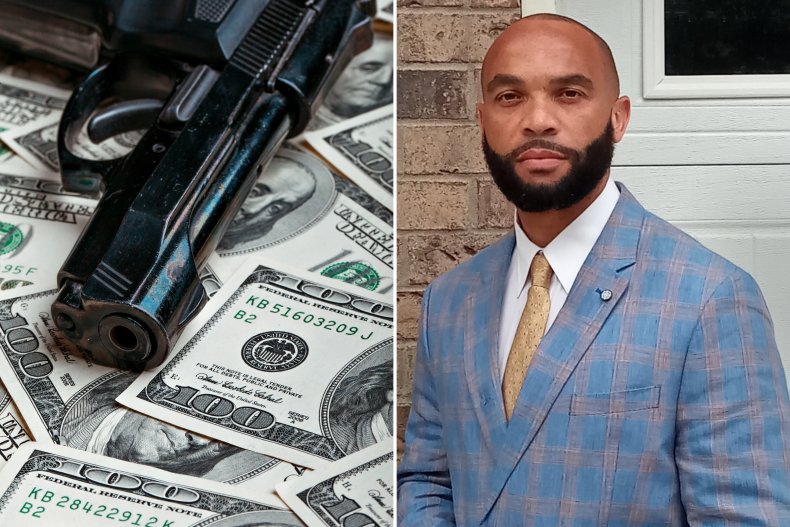

I began selling drugs for a living at the age of 21. The money was easy, fast and plentiful. There was no end in sight. But that didn't mean it wasn't coming.

I was introduced to the drug business by an older guy from Queens, New York. He and his girlfriend lived in the same apartment complex as myself and mine. He had two cars, loud music and nice clothes. All the things that I didn't have, but wanted at that age.

I always noticed that he was home when I left for work and when I got home. He was always coming and going and had a steady stream of people going in and out of his apartment. At that time I was ignorant of the wild ways of the world and did not recognize what was going on.

One day, after smoking a blunt with me, he asked if I was interested in making some extra money. I couldn't say yes fast enough.

A week later I was driving a 55 gallon hefty bag full of marijuana back to Tennessee from North Carolina. In the following weeks I was schooled in the weed business and my entrepreneurial dreams came to life.

I quit the job that my girlfriend got me at a local pizza shop. I spiced up my wardrobe, car and lifestyle so I could look the part. I began to see unbelievable amounts of cash day in and day out.

I earned as little as $3,000 per week. But when the high times were rolling I could make as much as $50,000 in that same span. I spent money just because I had it to spend.

At the end of many good days my thumbs would be sore and fingertips black from counting so much cash. I never knew that dirty money was actually dirty until then.

I was raided by S.W.A.T and taken to jail on three occasions. Infrared beams dotted the chests of my girlfriend and our children like chicken pox. Guns were pulled on me when I tried to collect drug debts.

My home was burglarized numerous times by robbers looking for my stash of cash or drugs, or both. My relationship with the mother of my children was poisoned with the possibility of me being sent away for decades at any moment.

She stayed by my side until it happened. She was even named a co-conspirator and sentenced to two years in prison. The damage that I caused her and our children can never be repaired.

Not once during this period of my life did I even try to understand the hurt and harm that I brought to my community. I justified the fact that I sold poison for profit by comparing it to what the government did with alcohol, tobacco and prescription pills.

It wasn't until I began working a normal job, like a normal person, but in an abnormal place, I began to piece the puzzle together and see the bigger picture.

Since the age of 16 I maintained a job, from bagging groceries to stocking shelves and cooking pizzas at fast food restaurants. I even sold Kirby vacuum cleaners. But the fast life I was living put that world far behind me rather quickly. I took on a high and mighty view of myself in the underworld.

My view of "regular jobs" and the people that worked them became warped. I couldn't see myself punching a clock ever again. Allowing some "broke ass" boss to tell me what to do and when to do it.

Having some nobody threatening to fire me if I didn't do what they said was less than enticing. How could I lower myself to work for people that come to see me at night to spend their entire paycheck for the weed or crack I was selling?

How could I allow myself to go from being this multi-state drug-dealer who plays with hundreds of thousands of dollars to being a regular ol' working man? A job was not in my future—or so I thought.

It's funny how life will find a way to force feed a man slices of humble pie when he least expects it. My slices came in the form of a sealed federal indictment. I was sent to Bristol Virginia Jail, and faced life in prison at the age of 28.

I would soon land in a new world, far from what's seen on Hollywood's big screen.

Imagine a strip mall with a big factory at the end and a four building apartment complex across the street. Add, in the distance, a community recreation center loaded with the latest fitness equipment and surround it all by a ten feet tall razor wire fence and you've got yourself a prison.

Days and weeks after hiding my tears and fears from other inmates, and suffering endlessly from boredom, I asked to become a trustee, meaning I took on certain duties around the prison without pay.

I was placed in the jail's kitchen, given an apron, a large spoon and told to stir huge pots of boiling slop. Over the course of a few weeks I had gone from turning my nose up at punching a clock for pay to working for free in the city jail. What a fall from grace.

Day-to-day life resembled that of an all-male college campus or military base. There were sports leagues and teams, pool and chess tournaments, and even movie night in the chapel every Friday. Every morning the prison came to life with a call to breakfast followed by one to work shortly after. That work call became the most important one to me, and hundreds of others.

Dangerous encounters flared up every blue moon, but were largely overshadowed by guys trying to find a way to cope with the mental pains of prison in peace.

Missing out on the lives of my young children was somehow made easier when I was able to escape from that harsh reality and lose myself in the work day. The work became therapy, and enabled me to cope with being in prison.

But it didn't stop there. Once I finally got to an actual federal prison after fighting my case for almost four years I went on the offensive. I sought out jobs. I worked as a janitor in the education department before becoming a GED instructor in the same building.

I taught Adult Continuing Education (A.C.E.) classes to men young enough to be my sons and others old enough to be a father. I worked as the equivalent of a busboy in the prison cafeteria cleaning up after messy inmate workers on their lunch breaks.

Some of them once held the same high-brow view of themselves that I had. Now here we all were sharing this space as quasi-slaves working for some of the lowest wages in the world.

As I rounded out the last years of my 15-year sentence I became an inmate worker advocate lobbying Congress for higher pay. I acted as a job recruiter of sorts actively seeking out qualified candidates to come work for $0.23 per hour in UNICOR, the prison factory, luring them in with the hope of one day earning just over $1 per hour. I was highly successful.

Over a 20-year span, my life had come full circle. All the skills I learned as a teen worker prior to selling drugs at age 21 were the same skills I used as an inmate worker in my thirties and forties at my prison job.

Ironically, I had become the Joe Blow and John Q that I had so regularly bashed and laughed at during my drug dealing days. It took my irregular job to land me in prison so that I could find the true value in being a working man.

Now that I'm almost free, living in home confinement and getting by on $15 per hour, I look at drug dealing in my forties the same way that I once looked at working in my twenties: I don't plan to ever do it again.

Aaron M. Kinzer is a writer, poet and former drug dealer.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.