Even though the campy, dayglow Barbie movie starring Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling will be fun to watch, I'll be cringing through it.

Mattel says the brand's purpose is to "inspire the limitless potential in every girl." But my memory is rooted in a time when Barbie presented only one image to emulate, and in my eyes, was not liberated in the least.

In 1959, the year Barbie was introduced to the world, I was 7 years old. I was fascinated by this tall, skinny doll. I could dress like my older brother's high school girlfriends or Hollywood movie stars.

There was something new and daring about Barbie with her high heels and glamorous clothes. She even sported big hard boobs like "the blonde bombshell" Marilyn Monroe.

Emboldened by Barbie's confidence and style, I started fantasizing about what my boobs would look like one day. Almost overnight, I went from pretending to be a mother for my Betsy Wetsy doll to dreaming about becoming a teenage siren.

While Barbie was a symbol of the new, post-war teen era, I believe she still embodied attitudes about women from the 1950s.

Ruth Handler, creator of Barbie, supposedly first modeled the doll's appearance on a popular "sex doll" made in Germany based on a cartoon character called Lilli. Lilli was sold in bars and tobacco kiosks as an adult novelty gag gift for men.

Barbie's many careers came later, but in the beginning her only aspiration was seemingly to be fabulous and catch a cute boyfriend. My mother loved Barbie, "the teenage fashion model," too. Perhaps more than I did.

One Christmas, she presented me with an entire Barbie wardrobe she'd sewn from McCall's doll patterns. There was a long, champagne-colored ballgown, daytime party dresses, and a cheerleader outfit mom made with a short, felt skirt.

She even knit a doll sweater with a big green "R" on it to represent Richwoods, where my brother went to high school. The only problem was, Barbie didn't have elbows, so we could never get her into the sweater.

Once the novelty of changing the doll's clothes wore off for me, I became bored. Plus, I was tired of trying to get Barbie to stand up on her two impossibly tiny feet without falling on her face.

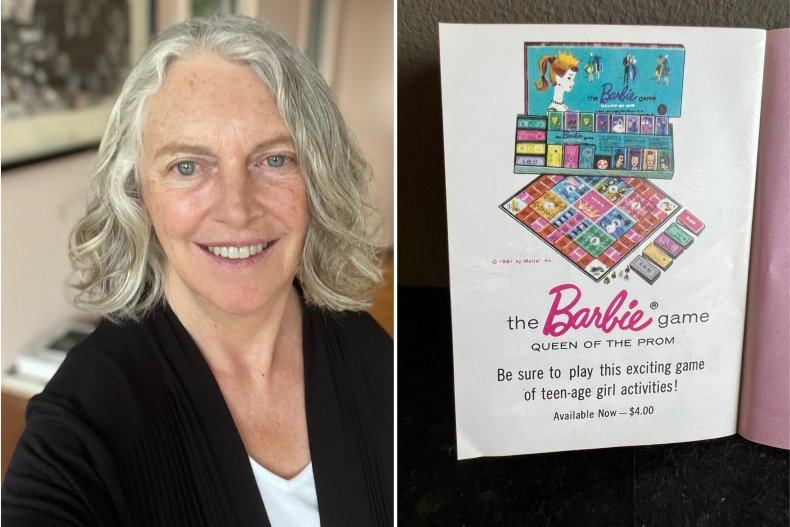

That's when I discovered a board game called "Barbie: Queen of the Prom." Rather than play with our dolls, my friends and I would compete for hours to see who could be the better Barbie.

In this game, Barbie's entire world was centered around climbing a social ladder to rule over everyone else. There were cards you could draw that either increased your chances of winning or held you back.

I'd panic if I got a card that said: "He criticizes your hair-do. Go to beauty shop" or: "You are not ready when he calls. Miss one turn."

While the game portrayed Barbie as vapid and boring, I have to admit it was a thrill to try to buy the best dress, snag the best boyfriend (Ken, of course), be elected as president of a school club to prove my popularity, and make a dash to be crowned queen of the prom.

I hadn't made it to middle school and already I was anxiously practicing strategies for social success.

According to my mother, a young girl's dreams should include going to a high school prom, pledging a sorority in college—something she couldn't afford to do—and joining the Junior League, once married with children, of course.

And that's probably what I would have done if it hadn't been for one person.

In 1963, a woman from my hometown of Peoria, Illinois challenged the status quo for women by publishing The Feminine Mystique. My mother was horrified that Betty Friedan was burning bras and causing a fuss, but "Aunt Betty," as my friends and I called her, was not to be stopped.

I felt caught in the middle, wanting to please my conservative mother yet desperately wanting to join the ranks of feminists for women's reform.

I was 11 years old by then and starting to understand that women were typically dismissed or derailed. A woman was not allowed to open a bank account or refuse sex with her husband, even if he was abusive.

Playboy Magazine was popular at the time, as was the TV hit "Leave it to Beaver". Women were depicted as playthings for men, necessary for raising a family, and kept below the glass ceiling at work.

They were supposed to be happy homemakers during the day then put on something sexy and greet their husbands after work with a Martini and a delicious home-cooked dinner.

I saw Barbie as a symbol of my mother's world. In a show of independence, one day I chucked my doll into a dark corner of my closet. This thrilling gesture marked my first rebellion against my family's expectations. I never looked back.

As a result, I totally missed Barbie's rise to social consciousness and diversity until I had my own daughter. In 2001, when she was 8 years old, my little girl wanted her own Barbie, and I caved.

By then, girls wanted to see themselves in the doll. My daughter immediately gave her new Barbie a short haircut and drew on her arms and legs with a ballpoint pen. It's Tattoo Barbie!

Little did I know this was a foreshadowing of my daughter's decision to get personal body art once she became a young adult. When I was young, it never occurred to me to do that.

Rather than take charge of my doll, I hid her.

A recent trailer for Barbie states that "if you love Barbie, or hate Barbie, this movie is for you." I may squirm in my seat, but I can't wait to watch the film with my millennial daughter and share our perspectives on how Barbie, and women, have changed—or not.

Ann Batchelder is an editor and author of the new memoir Craving Spring: A mother's quest, a daughter's depression, and the Greek myth that brought them together which will be published in October 2023.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.